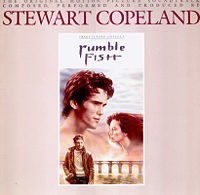

Rumble Fish: The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

| Rumble Fish: The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| |

| Soundtrack by Stewart Copeland | |

| Released: | 1983-MM-DD (USA)

1984-01-DD (UK) |

| Recorded: | 1982-1983 |

| Length: | ALBUM LENGTH |

| Label(s): | A&M |

| Producer(s): | Stewart Copeland |

| Studio(s): | Tres Virgos Studio |

Contents

Introduction

This section needs more information.

Personnel

This section needs more information.

Track listing

- . "Don't Box Me In" - 4:41

- . "Tulsa Tango" - 3:42

- . "Our Mother Is Alive" - 4:20

- . "Party At Someone Else's Place" - 2:26

- . "Biff Gets Stomped By Rusty James" - 2:27

- . "Brothers On Wheels" - 4:21

- . "West Tulsa Story" - 4:02

- . "Tulsa Rags" - 1:42

- . "Father On The Stairs" - 3:02

- . "Hostile Bridge To Benny's" - 1:57

- . "Your Mother Is Not Crazy" - 2:51

- . "Personal Midget/Cain's Ballroom" - 6:00

- . "Motorboy's Fate" - 2:03

Singles released

7" Singles

| Cover art | Catalog no. | A-side song/B-side song | Release date | Release country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM 2604 | "Don't Box Me In"/"Drama At Home" | 1983-MM-DD | UK | |

| AM 177 | "Don't Box Me In"/"Drama At Home" | 1984-01-13 | UK | |

| AMS 9757 | "Don't Box Me In"/"Drama At Home" | 1984-MM-DD | UK |

Variants, special editions and re-releases

This section needs more information. Images may be included to illustrate alternative cover artwork.

Charts

Album

| Year | Chart | Country | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| YYYY | CHART | COUNTRY | POSITION REACHED |

Singles

| Year | Song | Chart | Country | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YYYY | SONG | CHART | COUNTRY | POSITION REACHED |

Awards, nominations, and certifications

Awards

This section needs more information.

| Year | Winner | Award | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| YYYY | WINNER (album, song, producer, etc.) | AWARD (Grammy, People's Choice, etc.) | CATEGORY |

Nominations

This section needs more information.

| Year | Nominee | Award | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| YYYY | NOMINEE (album, song, producer, etc.) | AWARD (Grammy, People's Choice, etc.) | CATEGORY |

Certifications

This section needs more information.

| Country | Certifier | Classification | Certification |

|---|---|---|---|

| COUNTRY | CERTIFIER (RIAA, IFPI...) | CLASSIFICATION (Album, singles, foreign artist...) | CERTIFICATION (Gold, Platinum, Diamond...) |

Quotations and trivia

Engineer Robin Yeager remembers producing the soundtrack:

This project was the apogee of my recording career. Once you’ve done a soundtrack for a major motion picture (or a major director), albums music seems like a small effort. RumbleFish earned an Academy Award Nomination for best soundtrack.( It lost to Barbara Streisand's “Yentil”. Go figure!). The movie was directed by Francis Ford Coppola and starred Diane Lane, Mickey Rourke and Matt Dillon.

Pete Scott had been a long time friend of Richard Beggs. Richard had been a very fortunate studio owner in San Francisco. He owned a tiny Studio in the basement of a Flatiron building on the apex of Kearny and Columbus streets. Richard was fortunate because Francis Ford Coppola bought that building in the 70’s (I believe). Richard had a new client, a new business name (Zoetrope Studios) and went on to engineer Apocalypse Now as his first movie soundtrack . Pete’s friendship with Richard is what brought RumbleFish to Tres Virgos. Let there be no doubt. I was definitely ready for my first major motion picture soundtrack.

As luck would have it (and this business is mostly about luck), Richard was too busy with another project to take on the recording of the RumbleFish soundtrack. I would come to find out, it was a very labor intensive and time consuming thing to do. Pete invited Richard to the studio to check it out. We had the bare necessities compared to what it takes to do a film, but Richard agreed Tres Virgos would be adequate. We would need to rent some equipment (48 channels of Dolby, another 24 track to begin with) and we would need to wire it up. I asked Bob Missbach (who had left to become Jim Gaines assistant at The Plant) if he could come back to help with the wiring and interfacing of the system. We didn’t have much time as the movie was wrapping up the shooting phase in Oklahoma.

Francis had selected Stewart Copeland, drummer for The Police, to compose the soundtrack. The method of selecting Stewart was an interesting one. As Stewart told me, Francis wasn’t getting what he wanted from the film as its Director. The movie was closely tied to Time. Clocks were prominent in the movie. Clouds ran overhead at high speed. Surreal, black & white, Time. Francis asked his son, Roman, if he knew of any good drummers. His idea was to have a drummer on the set at all times to help build the importance of time and rhythm. It would help Mickey Rourke, Diane Lane and Matt Dillon (Tom Waits is in there too!) to achieve what Francis was trying to communicate artistically. Roman said sure he knew of a good drummer. If Francis wanted a drummer, his son would recommend only the best. A call was put out immediately to A&M Records in LA (this was before Stewart, Miles and Ian Copeland started IRS Records as the Police’s home record company) to find Stewart Copeland.

Stewart was located at his home England. The Police had just finished the Synchronicity (or was it Ghost In The Machine?) album and there was some time before the tour would begin. Stewart went to Tulsa, OK, set up his drums on the set and played! It was what Francis was looking for.

Stewart began to gently lobby to do the soundtrack for the movie. I believe Francis’ father, Carmine, was expected to do the soundtrack originally. Francis allowed Stewart to go into Zoetrope with Richard to demo a few scenes so he could make a decision on who claimed the composition rights. (The picture of Stewart playing guitar in front of a Marshall amp that came inside the original vinyl album jacket, was taken at Zoetrope as he was demo-ing a fight scene being shown on the screen in the background). Francis gave Stewart the nod, much to Stewart’s pleasure.

We rushed to accommodate all that was needed to transform TVS into a soundstage. Missbach finished up the interfacing of the Dolby and additional 24 track (Ampex ATR 124) and a Q-Lock synchronizing system was also installed (and boy was that thing a pain in the ass!). The Tama drum company started delivering sets of drums. Stewart’s favorite instruments started to arrive. Everything from a banjo to a xylophone!!

Stewart's personal assistant, Jeff Seitz, arrived to begin coordinating the instruments and setting up the drums and breaking them in. Jeff is one of the nicest people I have had the honor to meet. A graduate of Julliard and a trained timpanist, his New Jersey accent makes one think he’s a prizefighter. But what a gentle and intelligent man. I learned what a huge job it is to coordinate and assist the life of a major rock performer or movie star. These people require massive amounts of support to continue to operate on the level that they do. Jeff and I became good friends and stayed in touch for several years. Sadly, I’ve lost track of him and Stewart now.

When the day came for Stewart to arrive, we were good to go. He came into the control room with a tape. It was a rough mix of Peter Gabriel’s “Red Rain” on which Stewart had overdubbed the hi-hat pattern. He wanted to listen to the room and get used to it. He was pleased with the sound and the surroundings we provided. Tres Virgos was finished in Pecan Wood paneling and was a warm environment. He and Jeff conferred for a while in the music room. At these times (and purely out of respect for privacy) I always muted the monitors. From the looks of it, Stewart was comfortable and happy to see all of his instruments set up and miked.

The Tama drum kit was set up in the middle of our spacious music room. I had an AKG D12 close to the kick, AKG 452 (top & Bottom) on the snare, a 452 on the hat, three Roto-Toms were miked by one Neumann U87, a rack of about 4 or 5 Tube Toms ranging in size from 4” to about 8” with another 87, the three kit mounted toms each had Sennheiser 421s on top and Beyer 201s on the bottom, the two floor toms had Sennheiser 441s, AKG 414EBs 4’ apart overhead and two Crown PZM’s taped to the speaker soffit on the wall 12’ in front of the kit. 18 mics total. Even I thought this was a bit excessive, but wanted to hedge my bet and have fast options should I have needed them.

Also in the room was his Brazilian Gong Drum. A mighty piece of work about 30” in diameter and fitted to a stand. It had a leather skin on it and the beater was a padded leather ball on a stick. This was miked with a PZM on the floor. Poor Gordon! I will never forget when we were trying to get a level on the drum. I asked Gordo to double check the mic placement and as he did, Stewart (unaware that Gordon’s head was immediately beneath the drum) hit the drum to continue the level check. Gordon looked like he had just suffered an uppercut from Mohammed Ali himself. He stood up erect immediately and I could practically see the little tweety birds circling his head. He staggered back to the control room, assuring me the mic was in place.

Next we had the Xylophone. I used 2 more AKG 414EBs on it. I’ll always remember getting levels set on the Xylo. Jeff Seitz was playing Bach Sonatas on a Xylophone!!! Don’t forget, Jeff was a trained Timpanist from Julliard. Clearly, he’d learned his lessons well. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Jeff was also responsible for allowing me the time to get the drum tones set before Stewart got there. The guy is an awesome musician.

Our house piano (a Baldwin 8.5’ grand that had been in my family for 50 years or so) served its purpose quite well. Two PZM’s under the lid and a Neumann 87 several feet away. Nearly all of the thematic portions of the soundtrack were played by Stewart on that piano. In fact, except for the sax parts played by Mel Martin, the Harmonica played by Stan Ridgway and the string quartet, Stewart played everything on the soundtrack. The piano themes are very haunting in the movie.

Inside the control room we had the Oberheim Drum Machine (DX?), a Roland Synth of early vintage (and used throughout Police music), a Fender Precision Bass, Fender Telecaster and don’t forget the Banjo. I think we also had a Prophet 5 in there someplace. All of these were DI (Direct Input signal into the console patchbay).

30 inputs on a regular day. The MCI 528 was billed as a 32 input by 24 output console, but when all of the channel inputs were used it was a 64 input console. So I had room to spare. Only six efx send were available, but I could always use buss outs (giving me 32 efx sends) or Direct Outs (DO’s) (another 32). The beauty of inline consoles is that you can monitor everything in the mixdown mode. Each module is its own input and output module (hence the name I/O consoles a.k.a. inline). Whenever I worked on most English consoles I used the Monitor portion of the console for effect returns and tracked in the mixdown mode.

Through the great flexibility of the MCI I was able to handle most everything required in a fairly small space. Most other consoles were two times the size of an MCI. While I have loved other consoles (Trident “A” Range & 80C, API and Neve) for their sound, I truly loved my MCI. Plus, Ed Bannon had gone thru the entire console prior to opening the studio. He replaced all of the DBX VCA’s (Voltage Controlled Attenuators) with higher quality Aphex components. Chief Ed was to consoles what Boyd Coddington is to Hot Rods. Ed is a FREAK for phase coherency, thank God. The MCI had 48-volt power rails also which left plenty of headroom for increased dynamic range.

But I digress.

Stewart started with a couple of basic melodic themes played from the Roland Synth using the Oberheim DX as a rhythm box. He would program a rhythm pattern using the tambourine sound in the DX and add the synth part (usually a string sound). In this manner, he would demo the music and work it to fit the length and the dynamic of the scene. So, what he was doing was creating music for each scene of the movie as a demo track that would later be orchestrated and used as the final product. At the time it was the most logical way to work. With today’s technology it is easier to compose finished scenes all from the computer.

In 1983 automated consoles were not quite the norm they are today. The MCI was not automated, making it seriously interesting to work on each scene. While all of the inputs remained the same, the mix and the effects would change from scene to scene. The de facto method of tracking what is on each input at the console, was to use masking tape and a marking pen . Stretched across the entire length of the console, the engineer would label each input. In a typical setup, I listed the kick drum, snare, toms and overheads, keyboards, guitars, lead vocal, back up vocals and on through ending with Bass This was fine when you worked an album or commercial because you’d pretty much only use one piece of masking tape. A movie has SCENES, many many SCENES. As a result, each scene had it’s own masking tape stuck to the wall, and as we would work on one scene and then the next Gordon or I would grab the corresponding console tape off the wall and put onto the console (make damn sure you’re not one module off!). By the end of tracking the movie, we must have had 30-40 long pieces of tape stuck to the wall, each labeled with the scene name, like “Rusty walks to town” or “Fight Scene”, etc.

There was lots of “Punching In”. In multi track recording it is possible to fix mistakes made during the performance of any piece, because each instrument has its own isolated strip (about 1/16th of an inch) of the two inch wide tape. By rolling the tape back to a point a few bars before the mistake, the tape is started, the musician hears the music in the headphones and plays along and Bingo! The engineer hits the RECORD button at just the right moment and records an improved performance thereby fixing a mistake (or “Clam” as it is referred to affectionately). The engineer can then Punch Out by hitting the PLAY (or STOP) button saving the remainder of the performance.

Stewart was doing a percussion track. He was using a device that was a rigid wire strung with dozens of finger cymbals and was hitting it with drumsticks in a (fast) 1/32nd note pattern. He asked to stop the tape and go back so he could punch in and continue recording. Gordon (as always) was responsible for the 24 track operations. He wound back (a feat made exceptionally complicated by the ancient Q-Lock synchronizer) and took a fly at it. Oops, he missed it, please go back. Again…oops. This happened a few more times. Gordo rolled back farther than needed. In a fierce display of concentration, Gordo is now drumming his two index fingers in time to the rhythm pattern, on the face of the Auto locator (remote control for the 24 track) and next to the red RECORD button, Gordon deftly hit the RECORD button to his left. We were in! but now we had to get out! AGGGH! Gordon is fiercely drumming away still and trying to hit the PLAY button. Shit! Shit! Shiiiiit! “Hit it Gordo, hit PLAY!!” says I calmly (yeah right), “I’m t-t- trying” he stutters in time, “I’m t-t-ttrying!” Finally he jams a now numb index finger into the play button. Crisis averted. I open the talk back and ask Stewart if that take will do. Thank God he said yes!

Since we were working “to picture” we had video monitors scattered around the music room and one in the control room. The monitor in the control room was quite small, maybe a 15” or so.

The day had come for Francis to visit the studio to view/listen to the progress of the soundtrack. Bearing in mind that the speakers were UREI 813s (about a 4’x5’ box) and were powered by about 3000 watts of Crown amplification, we proceeded to play the first 20 minutes or so of the movie. Francis sat on the couch in front of the console watching the monitor. When we finished he stood up and said, “Great work! But next time I want (holds out his arms) a big picture and less sound!” oops. Well I guess when you’re Francis Ford Coppola you are more interested in the picture and how sound improves the image. If you’re Robin Yeager, you’re an audio engineer who strives to create an image from sound. Lesson duly noted for future (if there would be one after that!)

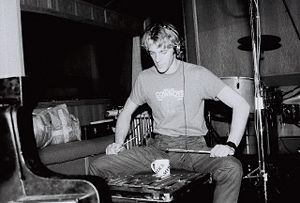

The studio was getting a very “lived-in” look about it. You could practically see the laundry strung across the control room. We would start at about 10:00 AM and work until we were finished, usually between 10:00 PM and midnight. Twelve hour days were easy back then.

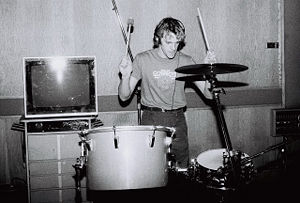

At last, the time came for Stewart to sit down at the drums and start the real stuff (as opposed to the Oberheim DX). I went thru the usual motions of getting the sounds of the kit together. Start with the Kick in quarter note sustained pattern. Snare, the same. Work thru all of it to get a good solid sound.

We’d been working for maybe 15 minutes, when Stewart said, “Could you hurry up! My hands aren’t calloused like they usually are!” Needless to say, I shot through the remainder of the drums. I worked on their sound as we rolled. Stewart started with regular drumsticks, but found that brushes worked well as a sound match to the film. He burned up the old fashioned metal brushes with ruberrized handle in about 10 minutes. Jeff Seitz went out and brought back some new heavier plastic brushes that really made the Toms snap and give great tonality. The plastic handles kept breaking, but we invested in a couple doze sets and made it thru the rest of the soundtrack that way.

I was getting enough sleep and generally arrived rested in the morning to take care of office business for an hour or so before entering the sanctity of the control room for the rest of the day. We always had a nice lunch brought in and probably dinner as well. Stewart was so concentrated on the soundtrack that he would eat very quickly and go back to work. This meant that Gordon and I would follow suit. The studio staff was benefiting nicely from the great food we were brining in. One day I decided to get a food that could not be hurried through. I asked for cracked Dungeness crab to be brought in. It worked! We all sat and patiently ate crab. I enjoyed that.

As the demo work of the film yielded to needing other musicians and/or outside help with orchestration to complete the work, Stewart asked if I knew of a good sax player to fill a Street scene. Mel Martin, sax and flute genius, got the call. Mel is known as a Jazz player, and has many credits for his work. He had done charts and performance for us and I had recorded a few albums for him.He was teaching in the east bay that night but could stop by on his way home after class. Great.

Mel shows up about 9:00PM with the usual compliment of instruments. His curved Soprano (the most kick ass sounding sop sax you’ll ever hear. Sorry Kenny.) his Tenor and I think an alto as well. After introductions were made we rolled the video of the scene with the existing track for Stewart and Mel to discuss. They arrived upon a musical direction for Mel to overdub an improvised Sop Sax part. We rolled back the tape to get the Q-Locks “pre-roll” out of the way and let it fly. Mel started playing, Listening only to the phones and not watching picture. His eyes closed, he shredded the take. When the take was finished, Mel opened his eyes and said “did I do ok?”. Stewart, Gordon and I were still so blown away by what he played, it took a few moments for any of us to respond. Mel said “I mean, I can do it again”. No Mel, that’ll do just fine thanks.

When an arranger was needed for string parts, I called Mel again. There was precious little time and even less notice for Mel to “whip out” string arrangements for an eight piece string section. He was up for several days straight and did a superb job. The normal small changes needed to be made, but the overall arrangements were just what Stewart wanted.

Bob Randles was the music editor of the movie. He pretty much lived with us in the studio operating his invention “Mu-Sync”. Mu-Sync tracked the scenes of the movie and the music as it pertained to each characters actions. It printed all of this information out on computer feed paper. In turn, it would sync to picture and sound helping Bob to identify particular points in the film where he might want to withdraw or change the soundtrack composition. This was Mu-syncs first actual test and it would crash and delay things once in a while. Mu-Sync would have been short lived in any case due to the innovations of computer music and synchronization to picture that were beginning at that time. Companies such as Synclavier and Fairlight changed the entire landscape of how many pictures are scored.

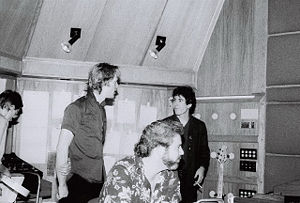

When the tracking was at last complete it was time to mix. For this we would go to Coppola’s Rutherford Zoetrope facilities in the Napa Valley. In what had been the attic of a wine barrel storage house, Francis installed a complete (and beautiful) film mixing room. With the projectors in back of us in isolated quarters, we would view each scene on the large screen and work on its mix. I was particularly grateful to Richard Beggs for allowing me to participate in this aspect of the production. I knew the tapes well and this provided help to Richard. While I was at the console with Richard and worked the soundtrack mix, it was clearly his experience and talent that yielded the final product. I was not involved in the Final Mix of the movie where Dialog, Music and Effects are all brought together for the end product. But I did mix all of the music.

Stewart and I had become good friends during this time. Shortly after our experience together, he and his (then) wife had their first child, a boy. Stewart sent me a card in the mail (which I still have) in his own handwriting announcing the birth. “It’s a Boy! We’re thinking of naming him Jordan Daniel Robin Yeager Copeland! Whaddya think?”

I also had one experience that made me really understand Jeff Seitz’ job just a bit better. Stewart wanted to go into town (San Rafael) to get a stopwatch. I volunteered to take him as I knew a sporting goods store that would have stop watches. We were inside for few minutes and I noticed people starting to recognize him. I was keeping an eye on them as Stewart scoped out stop watches and then some nice shades. When he handed his credit card to the cashier, he said something to effect of, “I thought that was you. You’re Stewart Copeland!” The store was getting frenzied. I told the cashier to complete his business so we could get out of there. He did, we did. A very small insight to what famous people have to cope with in the public.

When the time came to write the music for the credit roll at the end of Rumble Fish, Stewart called on Stanard Ridgway of Wall of Voodoo (Mexican Radio). Stan was on tour in Boston when he got the call to fly out to California. He left the stage, went to the Boston airport caught the red eye and arrived at the studio early in the morning. Armed with studio strength coffee, he and Stewart began to collaborate on the lyrics. “Don't Box Me In” was written and recorded in one very long day. We put Stan back on the plane for a 7:00 AM flight to meet the band on tour in New Jersey (I think). The mix that is used on the soundtrack album and the credit roll was actually a rough mix of mine to ½” tape done the next day. I don’t recall exactly why this was necessary to use my rough mix, but I believe that the 2” multitrack master tape was damaged in transit at some point. My rough was the only survivor.

See also

External links and reviews

References

source: Robin Yeager